The Lee Priory Gothick Library, James Wyatt (1746-1813)

The Lee Priory Gothick Library, James Wyatt (1746-1813)

Circa 1790

Sold

Please see below (and click link here) for a full description of The Library Ante-Chamber from Lee Priory kindly written by Professor Peter N. Lindfield

James Wyatt, the premier architect and designer of late Georgian Britain, largely followed the prevailing fashion — Neoclassicism. He spectacularly announced his arrival on London’s architectural scene by creating the Pantheon, Oxford Street, London (1769–72), in this style. Despite his success with Neoclassical forms and ornament, Wyatt was, apparently, ‘converted’ to Gothic by William Porden, the architectural advisor to the Earls Grosvenor, who later redeveloped Eaton Hall, Cheshire, as a Gothic mansion between 1802 and 1812. In support of his proposal to Gothicise Eaton, Porden writes to Robert Grosvenor that ‘in the year 1777 I seduced Mr. James Wyatt there who till then was little sensible of the beauties of gothic Architecture’. Whilst Porden’s Gothic architecture was ambitious and ornamentally sophisticated, Wyatt’s first Gothic works lack the rigour and architectural clarity of genuine medieval Gothic buildings. At Sandleford Priory, Berkshire (1780–9), for example, he casts the house in a sparsely-ornamented Gothic façade. The forms and motifs respond almost directly to the simplicity of Batty Langley’s plates published in Georgian Britain’s first Gothic Revival pattern-book: Ancient Architecture: Restored and Improved (1741–2), though Sandleford’s Entrance Hall features a chantry chapel-like passage.

In the same decade as his modifications to Sandleford for Elizabeth Montagu, the famed bluestocking, Wyatt began designing Lee Priory, Kent, for Thomas Barrett (Fig. 1). Externally, Wyatt created an exclusively Gothic home that is significantly more sophisticated in terms of architectural form, ornament and structure than his efforts for Montague. John Dixon’s painting of Lee (1785) illustrates its asymmetric form and abundance of Gothic flourishes (including an ornate oriel window, and a roofline bedecked with pinnacles and crockets). Instead of two-dimensional Gothic forms piercing stylistically-unrelated surfaces, as at Sandleford, Lee reveals Wyatt’s far clearer understanding of medieval architecture. Indeed, the octagonal Library’s exterior is modelled upon Batalha, a monastery in Portugal that Wyatt was certainly aware of, and whose form he later adapted for the crossing tower at Fonthill Abbey, Wiltshire. The development of Wyatt’s Gothic, in this sense, matches the most celebrated of Georgian ‘Goths’: Horace Walpole, whose Gothic villa, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, reveals his and his designers’ increasingly sophisticated and ambitious grasp of medieval architecture’s form and ornament.

Walpole was also heavily involved with Lee’s architecture and interior spaces. He first visited Lee on 28 August 1780, writing that ‘it is a small house improved by his Father, who bought Pictures, Miniatures, books, Missals, Prints &c. […] The present Mr Barrett has much improved the place under the direction of Richmond, Scholar of Browne, & has widened a little stream into a pretty River’. Later, in 1785, Walpole writes that ‘I have seen over and over again Mr Barrett’s plans, and approve them exceedingly. The Gothic parts and classic; you must consider the whole as Gothic modernized in parts, not as what it is — the reverse. Mr. Wyatt, if more employed in that style, will show as much taste and imagination as he does in Grecian’. Wyatt’s foreman, Mr Matthew, and one other were at Strawberry Hill on 25 May 1788, clearly exploring Walpole’s villa. On 5 June Walpole wrote to Barrett about this visit, stating that ‘If Mr Matthew was really entertained, I am glad — but Mr Wyatt has made him too correct a Gothic not to have seen all the imperfections and bad execution of my attempts; for neither Mr Bentley not my workmen had studied the science [of Gothic architecture], and I was always too desultory and impatient to consider that I should please myself more by allowing time, than by hurrying my plans into execution before they were ripe. My house therefore is but a sketch by beginners; yours is finished by a great master — and if Mr Matthew liked mine, it was en virtuose, who loves the drawings of an art, or the glimmerings of its restoration’. Walpole’s highly deferential letter does, nevertheless, indicate the undeniable failings — from a rigorously antiquarian perspective — of Strawberry Hill’s architecture and design. When Walpole visited Lee in 1790 he ‘found Mr. Barrett’s house complete, and the most perfect thing ever formed! Such taste, every inch so well finished, and the drawing room and eating room so magnificent! I think if Strawberry were not its parent, it would be jealous’.

Writing further about the interior based upon this visit, Walpole felt ‘it is the quintessence of Gothic taste, exquisitely executed — I wish William of Wickam were alive to employ and reward Mr. Wyatt — you would think the latter had designed the library for the former — it has sober dignity without prelatic pomp’. William of Wykeham supervised and administered architectural works for Edward III (including the reconstruction of Windsor Castle, Berkshire), making this very high praise indeed for Wyatt’s architectural ambition and mastery of Gothic forms.

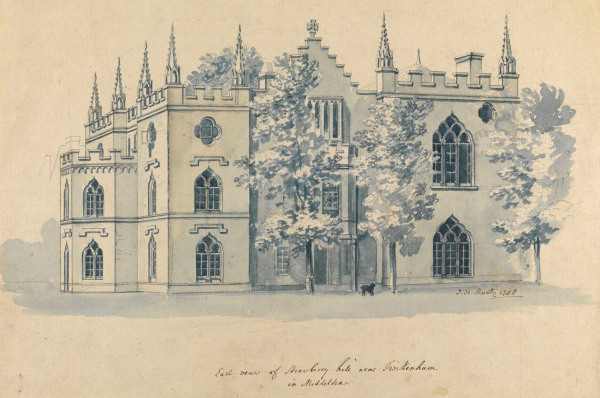

As indicated by Walpole’s letters, Lee Priory was presented repeatedly as an offspring of Walpole’s Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill (Fig. 2). Writing to Mary Berry in 1794, he declares that ‘you will see a child of Strawberry prettier than the parent, and so executed and so finished!’ The dwellings are connected, of course, by a shared appropriation of Gothic forms, though, unlike Strawberry Hill, only a handful of Lee’s rooms were Gothic. Despite the introduction of Neoclassical spaces, such as the Staircase hall, Lee’s debt to Walpole is expressed clearly by the only room that, until recently, was known to have survived the house’s demolition in 1954. The ‘Strawberry Room’, a small apartment at the far end of the enfilade on Lee’s piano nobile, was thought to be ‘a delicious closet too, so flattering to me!’ (Fig. 3) Indeed, Walpole considered the room ‘as perfect in its way as the library, and it would be difficult to suspect that it had not been a remnant of the ancient convent only newly painted and gilt — my cabinet, nay nor house, convey any conception; every true Gothic must perceive that they are more the works of fancy than of imitation’.

Today, the Strawberry Room is on permanent display in the British Galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Despite commonly-held opinion, fragment of a second room were salvaged from Lee before it was pulled down: they were saved by Dr Phillips, and later gifted to Stephen Weeks in 1986 who, in turn, passed them onto Bohemia, the monumental trust, in 2003. Thereafter, ownership of this miraculous survival transferred to Architectural Heritage, Gloucestershire. The fragments were drawn from the Ante-Camber to Lee’s octagonal Library — the room Walpole thought fit for an abbot: it ‘has the air it was intended to have, that of an abbot’s library, supposing it could have been so exquisitely finished three hundred years ago’. The Ante-Chamber connected the house’s Staircase Hall and the Library via a dogleg, and its appearance is recorded by John Carter when he surveyed the house in 1791, however he confusingly refers to it as the Saloon.

The fragments from this room now with Architectural Heritage comprise the Ante-chamber’s fan-vaulted ceiling (2.14 x 3.6 m) (Fig. 4), a pair of doors and door cases, and a suite of four enclosed bookcases (two narrow (marked A and C) and two double-width (marked B and E) (Fig. 5). Two missing bookcases (D and F), would complete the numbering sequence and create a symmetrical trio of bookcases (narrow–wide–narrow) on each side of the Ante-Chamber (Fig. 6). These fragments tally exactly with Carter’s depiction of the room now in the British Library, London. The Ante-Chamber was designed to correspond with the Gothic Library instead of the Neoclassical Staircase even though it is a quite separate from the octagonal room — it is essentially a linking passage and bookstore. Certainly designed by Wyatt, both the Library and its Ante-Chamber feature bookcases with the same repeating gallery of strawberry-leaf finials and richly cusped lower door panels below a diaper-encrusted dado. The only significant difference between the Library and Ante-Chamber bookcases is the treatment of the upper shelves: in the Library they are open and simply ornamented at the head with repeating cinquefoil-cusped arch heads. The Ante-Chamber bookcases, on the other hand, are entirely enclosed behind doors that on the upper register are similarly ornamented with cinquefoil cusped arches (blind). Lee’s bookcases are very important and quite early examples of painted Georgian Gothic furniture: reds and blues pick out the micro-ornamental detail, particularly on the cusped panelling, exactly as per Lee’s Library presses. They are in the same mould as other Gothic Revival painted furniture — particularly where colours are used to emphasise ornamental detail, including the seat furniture at Shobdon Church, Herefordshire (c.1755), the Pomfret Cabinet designed for Easton Neston, Northamptonshire (1752–53), and one of a suite of hall chairs from Enmore Castle, Somerset, commemorating the marriage of John Perceval (1711–70), second Earl of Egmont, to Catherine Compton in January 1756. Walpole also acquired blue and white barber-pole painted Welch chairs from Dickie Bateman’s house, the Priory, Old Windsor, Berkshire, in 1774, which he displayed in Strawberry Hill’s Star Chamber.

Very Much like Barrett’s Strawberry Room, which was tucked away in the south-east corner of Lee, the Library Ante-Chamber is a modest apartment. Both rooms, however, have a fan-vaulted ceiling made loosely in imitation of the most famous and widely recreated vaulting in Georgian Britain: the fan vaulting in Henry VII’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey, which directly inspired the Gallery’s ceiling at Strawberry Hill. The Library Ante-Chamber (2.14 x 3.6 m) is smaller than the Strawberry Room (2.21 x 5.72 m), however its vaulting is not pared back. Instead, the Ante-Chamber’s vaulting is extremely complex — more so than the Library’s — and equals that in Strawberry Hill’s Gallery. In a highly unusual move on Wyatt’s part, the Ante-Chamber ceiling combines both fan- and tierceron vaults — something not knowingly attempted before in Georgian Britain. Coupled with the highly decorative blind panelling, Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber demonstrates the cultivated range of architectural forms influencing Wyatt’s Gothic derived from studies and restorations of medieval architecture.

The fragments from Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber, consequently, are important remains from a house central to the late eighteenth-century Gothic Revival. They connect two of the most famous Gothic Revival houses: Strawberry Hill (via Walpole) and Fonthill Abbey (via Wyatt) and record Wyatt’s work on a modest, though architecturally informed and ambitious, project. Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber is a snapshot of Wyatt’s pre-Fonthill and Ashridge Park Gothic, and it significantly overhauls our understanding of his imaginative and scholarly engagement with medieval forms. It reveals that, unlike the Strawberry Room, Wyatt pursued an ambitious and densely decorative programme in what is essentially a small thoroughfare opening into Barrett’s Gothic Library.

James Wyatt, the premier architect and designer of late Georgian Britain, largely followed the prevailing fashion — Neoclassicism. He spectacularly announced his arrival on London’s architectural scene by creating the Pantheon, Oxford Street, London (1769–72), in this style. Despite his success with Neoclassical forms and ornament, Wyatt was, apparently, ‘converted’ to Gothic by William Porden, the architectural advisor to the Earls Grosvenor, who later redeveloped Eaton Hall, Cheshire, as a Gothic mansion between 1802 and 1812. In support of his proposal to Gothicise Eaton, Porden writes to Robert Grosvenor that ‘in the year 1777 I seduced Mr. James Wyatt there who till then was little sensible of the beauties of gothic Architecture’. Whilst Porden’s Gothic architecture was ambitious and ornamentally sophisticated, Wyatt’s first Gothic works lack the rigour and architectural clarity of genuine medieval Gothic buildings. At Sandleford Priory, Berkshire (1780–9), for example, he casts the house in a sparsely-ornamented Gothic façade. The forms and motifs respond almost directly to the simplicity of Batty Langley’s plates published in Georgian Britain’s first Gothic Revival pattern-book: Ancient Architecture: Restored and Improved (1741–2), though Sandleford’s Entrance Hall features a chantry chapel-like passage.

In the same decade as his modifications to Sandleford for Elizabeth Montagu, the famed bluestocking, Wyatt began designing Lee Priory, Kent, for Thomas Barrett (Fig. 1). Externally, Wyatt created an exclusively Gothic home that is significantly more sophisticated in terms of architectural form, ornament and structure than his efforts for Montague. John Dixon’s painting of Lee (1785) illustrates its asymmetric form and abundance of Gothic flourishes (including an ornate oriel window, and a roofline bedecked with pinnacles and crockets). Instead of two-dimensional Gothic forms piercing stylistically-unrelated surfaces, as at Sandleford, Lee reveals Wyatt’s far clearer understanding of medieval architecture. Indeed, the octagonal Library’s exterior is modelled upon Batalha, a monastery in Portugal that Wyatt was certainly aware of, and whose form he later adapted for the crossing tower at Fonthill Abbey, Wiltshire. The development of Wyatt’s Gothic, in this sense, matches the most celebrated of Georgian ‘Goths’: Horace Walpole, whose Gothic villa, Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, reveals his and his designers’ increasingly sophisticated and ambitious grasp of medieval architecture’s form and ornament.

Walpole was also heavily involved with Lee’s architecture and interior spaces. He first visited Lee on 28 August 1780, writing that ‘it is a small house improved by his Father, who bought Pictures, Miniatures, books, Missals, Prints &c. […] The present Mr Barrett has much improved the place under the direction of Richmond, Scholar of Browne, & has widened a little stream into a pretty River’. Later, in 1785, Walpole writes that ‘I have seen over and over again Mr Barrett’s plans, and approve them exceedingly. The Gothic parts and classic; you must consider the whole as Gothic modernized in parts, not as what it is — the reverse. Mr. Wyatt, if more employed in that style, will show as much taste and imagination as he does in Grecian’. Wyatt’s foreman, Mr Matthew, and one other were at Strawberry Hill on 25 May 1788, clearly exploring Walpole’s villa. On 5 June Walpole wrote to Barrett about this visit, stating that ‘If Mr Matthew was really entertained, I am glad — but Mr Wyatt has made him too correct a Gothic not to have seen all the imperfections and bad execution of my attempts; for neither Mr Bentley not my workmen had studied the science [of Gothic architecture], and I was always too desultory and impatient to consider that I should please myself more by allowing time, than by hurrying my plans into execution before they were ripe. My house therefore is but a sketch by beginners; yours is finished by a great master — and if Mr Matthew liked mine, it was en virtuose, who loves the drawings of an art, or the glimmerings of its restoration’. Walpole’s highly deferential letter does, nevertheless, indicate the undeniable failings — from a rigorously antiquarian perspective — of Strawberry Hill’s architecture and design. When Walpole visited Lee in 1790 he ‘found Mr. Barrett’s house complete, and the most perfect thing ever formed! Such taste, every inch so well finished, and the drawing room and eating room so magnificent! I think if Strawberry were not its parent, it would be jealous’.

Writing further about the interior based upon this visit, Walpole felt ‘it is the quintessence of Gothic taste, exquisitely executed — I wish William of Wickam were alive to employ and reward Mr. Wyatt — you would think the latter had designed the library for the former — it has sober dignity without prelatic pomp’. William of Wykeham supervised and administered architectural works for Edward III (including the reconstruction of Windsor Castle, Berkshire), making this very high praise indeed for Wyatt’s architectural ambition and mastery of Gothic forms.

As indicated by Walpole’s letters, Lee Priory was presented repeatedly as an offspring of Walpole’s Twickenham villa, Strawberry Hill (Fig. 2). Writing to Mary Berry in 1794, he declares that ‘you will see a child of Strawberry prettier than the parent, and so executed and so finished!’ The dwellings are connected, of course, by a shared appropriation of Gothic forms, though, unlike Strawberry Hill, only a handful of Lee’s rooms were Gothic. Despite the introduction of Neoclassical spaces, such as the Staircase hall, Lee’s debt to Walpole is expressed clearly by the only room that, until recently, was known to have survived the house’s demolition in 1954. The ‘Strawberry Room’, a small apartment at the far end of the enfilade on Lee’s piano nobile, was thought to be ‘a delicious closet too, so flattering to me!’ (Fig. 3) Indeed, Walpole considered the room ‘as perfect in its way as the library, and it would be difficult to suspect that it had not been a remnant of the ancient convent only newly painted and gilt — my cabinet, nay nor house, convey any conception; every true Gothic must perceive that they are more the works of fancy than of imitation’.

Today, the Strawberry Room is on permanent display in the British Galleries at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Despite commonly-held opinion, fragment of a second room were salvaged from Lee before it was pulled down: they were saved by Dr Phillips, and later gifted to Stephen Weeks in 1986 who, in turn, passed them onto Bohemia, the monumental trust, in 2003. Thereafter, ownership of this miraculous survival transferred to Architectural Heritage, Gloucestershire. The fragments were drawn from the Ante-Camber to Lee’s octagonal Library — the room Walpole thought fit for an abbot: it ‘has the air it was intended to have, that of an abbot’s library, supposing it could have been so exquisitely finished three hundred years ago’. The Ante-Chamber connected the house’s Staircase Hall and the Library via a dogleg, and its appearance is recorded by John Carter when he surveyed the house in 1791, however he confusingly refers to it as the Saloon.

The fragments from this room now with Architectural Heritage comprise the Ante-chamber’s fan-vaulted ceiling (2.14 x 3.6 m) (Fig. 4), a pair of doors and door cases, and a suite of four enclosed bookcases (two narrow (marked A and C) and two double-width (marked B and E) (Fig. 5). Two missing bookcases (D and F), would complete the numbering sequence and create a symmetrical trio of bookcases (narrow–wide–narrow) on each side of the Ante-Chamber (Fig. 6). These fragments tally exactly with Carter’s depiction of the room now in the British Library, London. The Ante-Chamber was designed to correspond with the Gothic Library instead of the Neoclassical Staircase even though it is a quite separate from the octagonal room — it is essentially a linking passage and bookstore. Certainly designed by Wyatt, both the Library and its Ante-Chamber feature bookcases with the same repeating gallery of strawberry-leaf finials and richly cusped lower door panels below a diaper-encrusted dado. The only significant difference between the Library and Ante-Chamber bookcases is the treatment of the upper shelves: in the Library they are open and simply ornamented at the head with repeating cinquefoil-cusped arch heads. The Ante-Chamber bookcases, on the other hand, are entirely enclosed behind doors that on the upper register are similarly ornamented with cinquefoil cusped arches (blind). Lee’s bookcases are very important and quite early examples of painted Georgian Gothic furniture: reds and blues pick out the micro-ornamental detail, particularly on the cusped panelling, exactly as per Lee’s Library presses. They are in the same mould as other Gothic Revival painted furniture — particularly where colours are used to emphasise ornamental detail, including the seat furniture at Shobdon Church, Herefordshire (c.1755), the Pomfret Cabinet designed for Easton Neston, Northamptonshire (1752–53), and one of a suite of hall chairs from Enmore Castle, Somerset, commemorating the marriage of John Perceval (1711–70), second Earl of Egmont, to Catherine Compton in January 1756. Walpole also acquired blue and white barber-pole painted Welch chairs from Dickie Bateman’s house, the Priory, Old Windsor, Berkshire, in 1774, which he displayed in Strawberry Hill’s Star Chamber.

Very Much like Barrett’s Strawberry Room, which was tucked away in the south-east corner of Lee, the Library Ante-Chamber is a modest apartment. Both rooms, however, have a fan-vaulted ceiling made loosely in imitation of the most famous and widely recreated vaulting in Georgian Britain: the fan vaulting in Henry VII’s Chapel, Westminster Abbey, which directly inspired the Gallery’s ceiling at Strawberry Hill. The Library Ante-Chamber (2.14 x 3.6 m) is smaller than the Strawberry Room (2.21 x 5.72 m), however its vaulting is not pared back. Instead, the Ante-Chamber’s vaulting is extremely complex — more so than the Library’s — and equals that in Strawberry Hill’s Gallery. In a highly unusual move on Wyatt’s part, the Ante-Chamber ceiling combines both fan- and tierceron vaults — something not knowingly attempted before in Georgian Britain. Coupled with the highly decorative blind panelling, Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber demonstrates the cultivated range of architectural forms influencing Wyatt’s Gothic derived from studies and restorations of medieval architecture.

The fragments from Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber, consequently, are important remains from a house central to the late eighteenth-century Gothic Revival. They connect two of the most famous Gothic Revival houses: Strawberry Hill (via Walpole) and Fonthill Abbey (via Wyatt) and record Wyatt’s work on a modest, though architecturally informed and ambitious, project. Lee’s Library Ante-Chamber is a snapshot of Wyatt’s pre-Fonthill and Ashridge Park Gothic, and it significantly overhauls our understanding of his imaginative and scholarly engagement with medieval forms. It reveals that, unlike the Strawberry Room, Wyatt pursued an ambitious and densely decorative programme in what is essentially a small thoroughfare opening into Barrett’s Gothic Library.